Grandad Cecil - A Magnificent Man

When I began tracing my family tree I concentrated on my father's side - like others I was driven by the idea of tracing my own surname back as far as possible. This was probably a mistake: my paternal ancestors were in the main a solid, reliable lot. Carpenters, blacksmiths, wheelwrights etc. who lived their lives without travelling more than a few miles from their birthplace. They were an ultra stay-at-home bunch. To give just one example, they were one of the few families from their chapel in Billericay who didn't emigrate to America on the Mayflower.

Mum's family were different though. They were much more mercurial. They were constantly trying to better themselves. When they didn't end up bankrupt or in prison they raised the family status for a generation or so - until a later one over-reached themselves or succumbed to alcohol.

Grandad Cecil Gulliver was born when the family status was at a bit of a low. His paternal grandfather had died young, just as his father, Albert, was starting off in that most respectable of positions - a solicitor's clerk. It probably didn't help matters that, for a short while, Cecil's grandmother was suspected of poisoning her husband. Possibly it was this shadow on his respectability which persuaded Albert to move to London where he met his wife, Jane Miller.

Jane and Albert, Cecil's Parents.

Jane's father was a captain in the merchant navy; as a result, he was away from home for long periods. When his wife showed signs of mental illness she had been confined to a lunatic asylum where she had died. The children were brought up first by their maternal grandparents and then by a wealthy uncle. They never really had the chance to form close bonds with their father who had remarried (bigamously at first, but then with another ceremony after the death of his first wife). By the time Jane was an adult, her father had a new family.

Cecil and his brother Albert.

Cecil was born in 1900, the middle one of three children. His older brother became a chartered accountant and his younger sister married and raised a family. Cecil's father and brother both fought in WW1 and Cecil was keen to get in on the action. Aged 16, he ran away from home and joined up. Jane was furious and talked the army into discharging him - but they warned her that they would not be so accomodating a second time. Cecil ran away again - this time to the newly formed Royal Flying Corps and despite his mother's protests he was allowed to remain.

Cecil is the middle of the three men standing at the back.

Cecil joined the RFC on 27th February, 1917. His age is recorded as 18 years and one month but he was actually one year younger. He was given the service number 62776. He gave his trade on joining as 'Motor mechanic'.

In the RFC Cecil worked as groundcrew. He was a Fitter(Gen) with the rank A.Mech2. He said little to his children about his time in the RFC except to tell them a rather gruesome story: a plane returning to his base had fallen apart mid-air just as it passed over the airfield and Cecil was the first to reach the pilot. He said that the body was like a bag of jelly, with every bone broken.

Another story passed down in the family tells that Cecil was invalided out of the RFC just before being sent to the Dardanelles: the lorry he was travelling in crashed and he was thrown out of the back. He was in a coma for a week and then discharged as unfit for service. His service record shows this to be untrue - he remained in the RAF until 27th March, 1920. He was discharged on medical grounds though - mainly due to a hernia - but also due to concussion, so maybe he really had fallen off the back of the lorry!

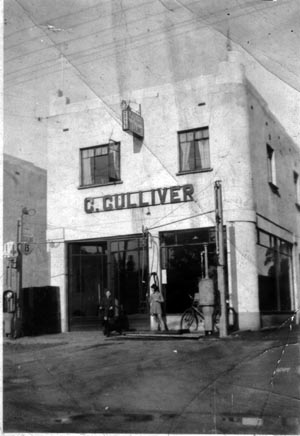

Cecil's Garage at Eastwood. After he emigrated it was renamed 'Lilliput Garage'.

After the war, Cecil had several jobs - including one as a bus driver on the Canvey - Leigh route (I have his drivers badge). He found timekeeping difficult, so started out on his own as motor mechanic in a rented barn at Woodcutters, Eastwood (next to a dog racing stadium). He had a reputation for being able to fix things that others couldn't. He did non-motor light engineering as well and made most of his motor parts.

From about 1926 he lived at Benvenue Avenue in one of a group of houses built (and rented out) by a market gardener. He didn't get on with the landlord's wife and moved about 1934 to Cockethurst Avenue. During the time they lived there, Mum had a year off school - possibly because of suspected tuberculosis.

The postwar period saw the beginning of widespread motor car ownership and so Cecil's business prospered and he was soon able to build a proper garage and workshop to his own, rather individual, design. It is said that the garage was largely built by local tradesmen paying off their unpaid garage bills in kind. The family moved to the new garage in Eastwood just before King's silver jubilee in 1935 (Mum remembered the bunting on the garage).

Violet Garner.

In 1922 Cecil had married Violet Garner whom he had met while ice-skating at Southend. The marriage got off to a rather bumpy start when Cecil discovered that Violet had lied to him about her age: instead of being younger, she was nearly three years older than him.

The couple had four children: Jean (who died in childhood), Yvonne(my Mum), Barbara and David.

David was only one when the second war started. The war had a devastating effect on the garage trade - petrol rationing led to most private cars being laid up 'for the duration'. During the early part of the war, they closed up the garage for a year and went to live with Cecil's parents in Surrey - during which time he worked for Marconi earning relatively high wages of £10 a week. When the bombing in Surrey got worse than at home, they returned to Eastwood where they found that all their possessions had been taken 'for safe keeping' by their neighbours. Cecil spent an awkward period going around and recovering his stuff.

Cecil reopened the garage. He also did contract work for the war effort. He made spindles which had to be delivered to the Royal Mint. Mum remembers driving up to London to make a delivery - the road was deserted with grass growing through the surface (as a result of petrol rationing and restricted entry into the prohibited area) - on the way back she could see the refineries on Canvey Island burning.

Cecil was an Air Raid Warden but suffered from poor night vision. Mum was enrolled as an ARP messenger but was never called upon to deliver a message.

Cecil standing outside Gulliver's Garage.

Cecil was a man of strong political opinions. The election of a Labour government after the war was the last straw and decided him to fulfil a long ambition to emigrate to New Zealand with his wife and two younger children. Many of his friends found it amusing that Cecil arrived in New Zealand just as the people there elected Labour for the first time.

In New Zealand, Cecil first worked as a mechanic, but when he had raised sufficient funds he built himself a house and a shop which he ran as a general stores.

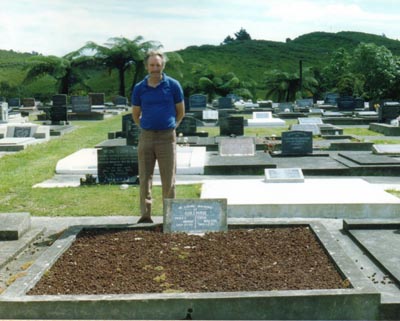

In 1963, Cecil was ill in hospital when Violet had a stroke and died. Before receiving the news, her daughter Yvonne (who lived in England) dreamed the she was floating past a giant illuminated Christmas tree. Shortly afterwards she received a photograph from New Zealand showing the same tree in the square opposite her mother's house, past which she would have been carried on her way to hospital. Cecil lived on for a few years more, until his death in 1971. They are buried in the cemetery at Whakatane.

David Gulliver standing by his parents' grave.